The great flood of 1964, which took out bridges, roads, and homes, and submerged dozens of square miles of the Flathead in June of that year, is the definitive flood for our valley. But we have experienced other floods of note, among them the inundations of 1894, 1916, 1933, and 1948.

Recently, another major high water event in the Flathead came to light — the late winter flood of 1900 — thanks to researchers from the Milbourne Institute of Flood Studies, who used rare photographs of the swollen Flathead River to reconstruct the flood’s hydrograph.

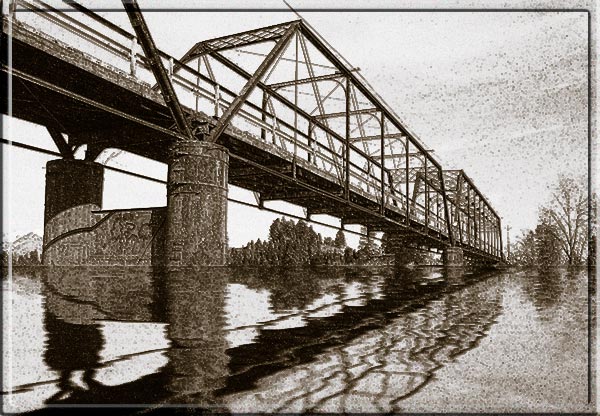

Above, the Spencer Attwood photograph that provided Dinhoui and his colleagues with the river height information that led to the reconstruction of the flood’s hydrograph.

“In one respect, we were the beneficiaries of Lady Luck,” said Milbourne Professor of Hydrology Dr. Aleister Dinhoui, a specialist in historical flood studies. “We found some very well preserved, uncatalogued photographs of the flood taken by Minneapolis photographer Spencer Attwood, who was on assignment for the Great Northern Railroad. The Old Steel Bridge east of Kalispell was in one of the photographs, so we were able to ascertain the the river’s height rather precisely. After that, it was all mathematics.”

Dinhoui reckons the river crested at 107,000 cubic feet per second at Columbia Falls on 29 February 1900. That would make it the third largest flood in Flathead history after the flood of 1964, which crested at 176,000 cfs, and the flood of 1894, which crested at an estimated 140,000 cfs.

“Apart from its size, what sets the winter flood of 1900 apart from most other Flathead floods is the time of year that it occurred. At the end of February, the river is usually at a winter low. We believe that an unusual combination of exceptionally warm and windy winter weather — there may have been a couple of days over seventy — coupled with gullywasher rains from back-to-back Pineapple Express weather systems, brought a tremendous amount of water down from the mountains in a very short time.”

Attwood’s photographs of the drowned bridge and flatlands were never published. According to notes in the box in which the prints was found, the railroad ordered the images destroyed so as not to alarm potential settlers. Attwood, however, could not bear to destroy images so dearly obtained, and secretly kept a set of prints for himself.

Dinhoui’s book on the discovery of the photographs and the reconstruction of the flood, A Wet Day in February, is scheduled to be published by the Milbourne Press at the end of August.