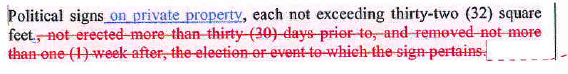

Still on Flathead County’s book of laws is an ordinance that prohibits political signs from being erected more than 30 days prior to an election, and requiring taking them down no later than one week after the election or event. It’s egregiously unconstitutional, and at long, long, last, the Flathead County Commission will, on Monday, 21 April, consider modifying the ordinance to bring it into constitutional compliance. Here’s the old and new (retained, black; new, blue; removed, struck-thru red):

An explanatory comment accompanies the proposed revisions:

These changes are based on court decisions concerning residential political signs, mainly Collier v. City of Tacoma, [and] City of Painesville Building Department v. Dworken and Bernstein Co.

Collier, a 1993 decision by the state of Washington’s supreme court, held that pre-election durational limits were unconstitutional, but that durational removal requirements were permissible. (Why Flathead County is relying on Collier instead of precedents in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals is a puzzle, but that’s an issue for another day.) A 1999 federal district court decision in Maryland, Curry v. Prince Georges County, disagreed with Collier on removal requirements:

10. A few courts have held that regulations requiring removal of signs following an election, as opposed to pre-election posting limitations, are permissible. See McCormack v. Township of Clinton, 872 F.Supp. at 1326; Collier v. City of Tacoma, 121 Wn.2d 737, 854 P.2d 1046, 1057 (Wash.1993). The problem with these decisions is they fail to consider when the post-election period ends and the next pre-election period begins. If an individual wishes to promote a candidate, the candidate’s cause, or both by posting a sign on residential property several months or years before the next political election, the logic of City of Ladue would certainly seem to permit it.

City of Ladue v. Gilleo, decided in 1994, held:

An ordinance of petitioner City of Ladue bans all residential signs but those falling within one of ten exemptions, for the principal purpose of minimizing the visual clutter associated with such signs. Respondent Gilleo filed this action, alleging that the ordinance violated her right to free speech by prohibiting her from displaying a sign stating, “For Peace in the Gulf,” from her home. The District Court found the ordinance unconstitutional, and the Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that the ordinance was a “content based” regulation, and that Ladue’s substantial interests in enacting it were not sufficiently compelling to support such a restriction.

Held: The ordinance violates a Ladue resident’s right to free speech. Pp. 4-16. [Syllabus]

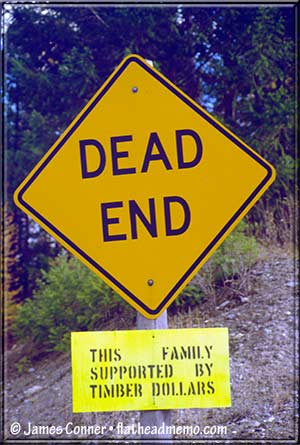

An important takeaway from Ladue is that not all political signs are related to an election. There’s no doubt in my mind that the This Family Supported by Timber Dollars signs that in the 1980s proliferated in the Flathead like dandelions in a horse pasture were political signs. Or that the hypothetical Impeach Barack Hussein Obama sign in the photo-illustration below would be a political sign and thus protected by the First Amendment.

There are two main reasons for imposing durational limits on political signs: (1) providing an advantage for incumbents, who are better known, and (2) reducing alleged visual clutter. The clutter reduction argument is especially revered by the community planning crowd, including some current leaders of the Flathead Democratic Party, although most self-appointed guardians of public beauty seldom seem equally ill-disposed toward the real estate for sale signs that, in my opinion, sully neighborhoods (but also serve as an indicator of economic trends).

The U.S. Supreme Court, to my knowledge, has never directly addressed the constitutionality of election related political signs. Therefore, the controlling law for Montana is from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. It’s complicated, but I believe the Ninth would strike down durational limits in Montana. So, too, I suspect, do Flathead County’s planners and legal experts, who undoubtedly want to avoid the expense and embarrassment of going to court to defend a lost cause.

As a practical matter, I think those who support durational limits because of aesthetic concerns have little to fear. Election signs lose their political punch after a few weeks, and even the new plastic signs don’t weather that well, so candidates have little incentive to put up their signs months in advance of the election. A few do, of course, most recently Republican county commissioner candidate Gary Krueger, and years before that legislative candidate Larry Baer. But most candidates prefer waiting until the start of voting approaches to plant their signs, as that’s when a sudden sea of signs has the greatest impact. And after the election? Both political parties quickly dispatch squads to collect the signs before they’re stolen or destroyed.

That leaves political signs that are not part of an election. Except in extraordinary circumstances, there won't be many. And in extraordinary circumstances, free speech is extraordinarily necessary and valuable.

The Flathead County Commission should change the law as proposed. You can use the commissioners’ contact form to send them a message supporting the removal of durational limits on political signs on private property.